As a United Methodist, I will be at our General Conference this coming Sunday. Only you know what to say in your context - but here was my best effort to preach directly into where we are a couple of Sundays ago ("Remember Your Baptism").

Genesis 45:3-11, 15, that profound narrative, for me the theological high water mark of the Old Testament and maybe all of Scripture, has come up recently in the lectionary: see my August 20 post for reflections and images. It would be hard to imagine a finer text for our broken denomination than this rich, miraculous story of reconciliation.

Genesis 45:3-11, 15, that profound narrative, for me the theological high water mark of the Old Testament and maybe all of Scripture, has come up recently in the lectionary: see my August 20 post for reflections and images. It would be hard to imagine a finer text for our broken denomination than this rich, miraculous story of reconciliation.

1 Corinthians 15:35-38, 42-50 continues the lectionary’s 3-week run on Paul’s climactic “resurrection” chapter. For this segment’s focus, I might add the importance of helping folks understand the “spiritual body” that is pledged in Jesus’ resurrection – huge, as people worry about lost loved ones, and their own futures. In The Life We Claim: The Apostles’ Creed for Preaching, Teaching & Worship, I explained it like this: “When we speak of the resurrection, we do not mean that Jesus’ soul survived the death of his body, and yet we do not mean the mere resuscitation of a corpse. The risen Jesus is not recognized, but then is recognizable. He can be touched, but then he pulls back. He materializes, and then he vanishes. Paul spoke of the resurrection as involving a spiritual body (1 Corinthians 15). A body, yes, but spiritual, not merely a spirit, but a body, totally transformed, animated entirely by the Spirit, not liable to disease or death. So for those whose understanding of anatomy makes a resuscitation seem ridiculous, the Bible narrates something different, and far better – better even than the immortality of the soul. The Bible promises the resurrection of spiritual bodies. We can rejoice, even if we lack clarity on this matter: ‘The Church binds us to no theory about the exact composition of Christ’s Resurrection Body’ (Dorothy Sayers).”

And then, our Gospel: Luke 6:27-38, continuing last week’s opening of Jesus’ “Sermon on the Plain,” paralleling but adjusting a bit from Matthew’s “Sermon on the Mount.” It isn’t entirely sufficient when Christians use slogans like “Love Wins” (although, of course, it does) – as we’re still in the mode of love-as-my-preference/desire. Jesus envisions a love that is commanded; love can be and is commanded! Kierkegaard probed this deeply in Works of Love – a bit of a testimony to his own dark experience of rejected love. Luke translates Jesus (who spoke in Aramaic!) as speaking of agapé, unconditional, giving, fixed on the good of the other love. No reciprocity with Jesus: he does not say Do unto others so they will do unto you!

To

illustrate the radicality, Jesus says we love enemies, and beggars. Who are our

enemies? We might picture strangers or dangerous people; Jesus’ first listeners

might have growled at the Roman or tax collectors. But perhaps the enemies we

must love are within the church (given our divisions…) – and maybe even (not to

psychoanalyze) within my own soul. Amy-Jill Levine humorously recalls

that moment in Fiddler on the Roof when the rabbi of Anatevka was asked “Is

there a blessing for the Czar?” Yes: “May God bless and keep the Czar… far away

from us!”

Ben Witherington, reflecting on

Jesus and forgiveness, tells a

story he heard Corrie ten Boom tell – how she encountered the Nazi who

had treated her sister brutally, leading to her death, and found forgiveness

for him. Jesus’ most ignored commandment might just be “Do not judge.” We

should be relieved that this terrible burden is not laid on us; maybe the key

to love within the church, and to those outside, is precisely refraining from

judgment.

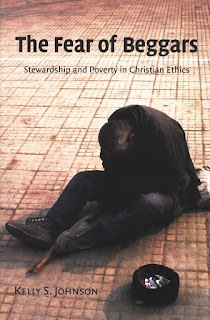

Jesus also speaks of love of beggars: “Give to everyone who begs from you” (which poses daunting challenges, and doesn’t entirely answer how we give to them). Kelly Johnson has gifted us with a marvelous book on the history and theology of begging: The Fear of Beggars: Stewardship and Poverty in Christian Ethics. Beggars make otherwise invisible poverty visible, unavoidable. Yes, begging can be sloth or avarice, but the beggar still is always a challenge to holiness, wealth, generosity. In the Middle Ages, the Dominicans and Franciscans, chose to become beggars – in solidarity with the poor, and deliberately distancing themselves to the church’s corruptions with wealth. John Wesley saw beggars as a question: “The Lord has lodged money in your hands temporarily; what return will you make?” And Peter Maurin, Dorothy Day’s mentor, repeatedly said “What we give to the poor for Christ’s sake is what we carry with us when we die.”

Yes, we have to parse dependencies, and how we contribute through agencies. But we can always be kind to the poor, to beggars, giving them the gift of love. Marion Way, a great friend and longtime missionary in Brazil, would always stop when encountering a beggar, ask the person’s name, lay hands on him and pray.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.