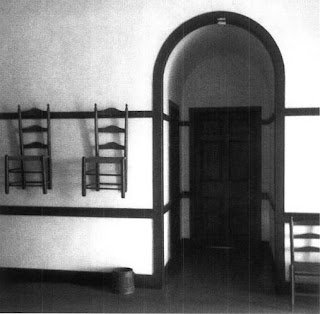

My plan had been to preach through Genesis this summer, tracing the lectionary route. But while I’m happy to tackle any text, Genesis 24, about this curious courtship, gazing at her carrying water, she spies him lifting heavy things in the field, and then the climactic verse I dare you to make into a sermon: “I put the ring on her nose” (Genesis 24:47). Plus it’s so long-winded. I think I will instead pair Romans 7:15-25a with Matthew 11:16-30. And I think I'm going to position a chair up in the altar area - and find my way toward what Thomas Merton wrote when he was photographing a Shaker village:

"The peculiar grace of a Shaker chair is

due to the fact that it was made by someone capable of believing that an angel might come and sit on it."

Scholars argue

over the main point of Romans 7. Who is

the “I” who is speaking? Is Paul

speaking autobiographically?

Representatively? Is he speaking of his Jewish experience outside of/prior

to Christ? Or his life in Christ? To me,

the pre-conversion Saul/Paul strikes me as a man utterly devoid of struggle; I’m

fond of the idea that faith isn’t the resolution of struggle, but the

introduction of, the inducement of newer, deeper struggles.

Michael Gorman

and many others may be right when they conclude that the “I” in Romans 7 is

simply unredeemed humanity. But really,

for me as a Christian, and as I try to serve as a pastor, it rings entirely

true that “I do not understand my own actions; I do not do what I want, but the

very thing that I hate.” Oh, I suppose

we all preach to those who feel confident, have a sunny disposition, and find

ways to justify themselves. But the

serious, biblical Christian, striving for holiness (inner and outer) in an

unholy world and with what T.S. Eliot called our moral “shabby equipment, badly

deteriorated,” will get it. How does the

pastor gently but surely invite the sunny, self-justified into Paul’s struggle?

Romans 7 is a

text that is probably better read aloud, slowly, that explained. And yet little asides might assist. “Nothing good dwells in me.” I love Winston Churchill’s bon mot: on

hearing a sermon on “I am a worm,” Churchill mused, “Yes, and I am a glowworm.” We are worms indeed, but depending on your

theological, denominational foundation, you may be able to see that the

experience of “Nothing good dwells in me” is only possible because there is a

glow in there, the image of God hanging on by a thread but not entirely

vanquished, or we would never imagine that “nothing good dwells in me.”

“When I want to

do right, evil lies close at hand.” Sin

isn’t rule-breaking or being human. Sin

is a personal, aggressive vulture-like force.

Surely Paul would have imagined that tragic moment in Genesis 4: when

Cain’s jealousy was kindled, the Lord said to him, “Why are you angry? If you do well, will you not be accepted? And

if you do not do well, sin is couching at the door; its desire is for you, but

you must master it.” Walter Brueggemann,

probing this moment in his Genesis/Interpretation

commentary, draws our attention to John Steinbeck’s East of Eden, which

discusses this very text, then concluding: “It is easy out of laziness, out of

weakness, to throw oneself onto the lap of the deity, saying ‘I couldn’t help

it; the way was set.’ But think of the glory

of the choice! That makes a man a

man. A cat has no choice, a bee must

make honey. There’s no godliness there.” Steinbeck is perhaps more confident than Paul

in the human ability to choose well. The

preacher is wise to explore the ambiguity – which people feel, surely.

Of course, as a Lord of the Rings fan, I am drawn to the flashback scene in The Return of the King where Sméagol kills Deagol over the ring of power (watch here!). Tolkien was surely envisioning not just Cain and Abel but also the bondage of the will according to Paul.

I love the way

Paul narrates his mounting frustration, building up to this exasperated yelp: “Wretched

man that I am! Who will deliver me from

this body of death? Thanks be to God…” This will preach. Once we plunge deeply enough into our abject

inability to do God’s will or to be whole people, then at the bottom of that

pit we cry out… and then have good cause to give thanks to God.

This kind of

spiritual labor is exhausting. Perhaps

it is only once you have exhausted your own resources, once you realize how

weary you are of your muscular, self-reliant, grittily determined, Atlas-like

life, can you finally just rest and be delivered. Here is Jesus’ reply to the people who

understand Romans 7. “Come to me, all

who labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for

I am gentle and lowly in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy, my burden is light”

(Matthew 11:28-30). Brueggemann (in his

fantastic Sabbath as Resistance) wryly says that Jesus is speaking here in his “sabbath

voice.” We don’t know tone of voice or

facial expression, but it’s worth trying to depict Jesus’ immense mercy and

gentleness, his profound, inviting affection for worn out people. Go deeply with this. I sometimes report that, in counseling, I

often ask people, “Tell me one adjective to describe how you feel.” The #1 answer I get is “I am tired.” No wonder.

Our culture is a rat race, a constant press of busyness and never doing

or having or being enough. Sometimes

church contributes to the tension and weariness…

Back to that Shaker chair. A chair, a bench - all kinds of images suggest Come and rest, come and sit. When Pope Francis began his work, he brought a chair out to the Swiss guard posted outside his office and invited him to sit down. Lovely. Rest is so elusive. It's not about more vacations, or more time off. It's something deeper inside; Lincoln once said he suffered from a weariness that many good nights' sleep wouldn't cure. We need solitude, togetherness with God, making ourselves unavailable so we might be available to God. During the Montgomery bus boycott, somebody offered a ride to an elderly woman named Mother Pollard. She refused, saying "My feets is tired, but my soul is rested."

Back to that Shaker chair. A chair, a bench - all kinds of images suggest Come and rest, come and sit. When Pope Francis began his work, he brought a chair out to the Swiss guard posted outside his office and invited him to sit down. Lovely. Rest is so elusive. It's not about more vacations, or more time off. It's something deeper inside; Lincoln once said he suffered from a weariness that many good nights' sleep wouldn't cure. We need solitude, togetherness with God, making ourselves unavailable so we might be available to God. During the Montgomery bus boycott, somebody offered a ride to an elderly woman named Mother Pollard. She refused, saying "My feets is tired, but my soul is rested."

I wonder if the

whole notion of Sabbath is the best gift we can give our people – and to

ourselves. Not the “take more time off”

or “go on more vacations” or “maintain your boundaries” kind of faked

sabbath. Genuine sabbath, that is a

robust time of rest and joy, time for God and each other, time to get

disconnected from our gadgets so we can get connected to God and others. Eugene Peterson, in his memoir, The

Pastor, provided me a wake-up call regarding what I do day by day as a

minister, and as a person. Here are two

excerpts that may or may not help your sermon preparation, but will embrace you

with Jesus summons to you, as a person and as a pastor, to “Come to me, you who

labor and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest” – which is more important

than this Sunday’s sermon, and without which, this Sunday’s sermon won’t matter

much. Listen to Peterson:

“Instead of calling people to worship

God, pastors all over the country were inviting people to ‘have a worship

experience.’ Worship was evaluated on

the ‘consumer satisfaction scale’ of one to ten. It struck me as a violation of the holy, a

secularization of the sacred. Taking the

Lord’s name in vain. I determined to

reintroduce the rubric ‘Let us worship God’ for my congregation, and then

really do it. I knew this wasn’t going

to be easy. The entertainment model for

worship in America was pervasive. And

community. The church as a community of

faith formed by the Holy Spirit. Church

in America was mostly understood by Christians and their pastors in terms of

its function—what it did: build buildings, become “successful,” change the

neighborhood, launch mission projects, and create programs that would organize

and motivate people to do these things.

Programs, mostly programs.

Programs had developed into the dominant methodology of ‘doing church.’ Far more attention was given to organizing

and giving leadership to programs than anything else. But there is a problem here: a program is an

abstraction and inherently nonpersonal.

A program defines people in terms of what they do, not who they

are. The more program, the less

person. Church was understood not in

terms of personal relationships and a personal God but in terms of ‘getting

things done.’ This struck me as

violation of the inherent personal dignity of souls. The abstraction of a programmatic approach to

men and women, however well-meaning, atrophied the relational and replaced it

with the pragmatic. Treating souls for

whom Christ died as numbers or projects or resources seemed to me something

like a sin against the Holy Spirit. I

wanted to develop a congregation in which relationships were primary, a

household of hospitality. A community in

which men and women would be known primarily by name, not by function. I knew this wouldn’t be easy, and it wasn’t.”

And then this:

“I realized that I was gradually becoming

more interested in dealing with my congregation as problems to be fixed than as

members of the household of God to be led in the worship and service of

God. In dealing with my parishioners as

problems, I more or less knew what I was doing. In dealing with them as a

pastor, I was involved in mysteries, mostly having to do with God, that were

far beyond my understanding and control.

I had been shifting from being a pastor dealing with God in people’s lives

to treating them as persons dealing with problems in their lives. I was not being their pastor. I could have helped and still been their

pastor. But by reducing them to problems

to be fixed, I omitted the biggest thing of all in their lives, God and their

souls, and the biggest thing in my life, my vocation as pastor.”

************************************

** My newest book, Worshipful: Living Sunday Morning All Week, is available. My forthcoming book, Weak Enough to Lead: What the Bible Tells Us About Powerful Leadership, will appear before too long.

************************************

** My newest book, Worshipful: Living Sunday Morning All Week, is available. My forthcoming book, Weak Enough to Lead: What the Bible Tells Us About Powerful Leadership, will appear before too long.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.